I’m enjoying remembering that we had a summer! After a weekend in wellyboots and wearing my dry robe to muck out and poo pick at the livery yard, this morning, I had a meeting online that connected me again to Balsall Heath City Farm (BHCF). BHCF has been important to me in the past year (people, animals, space), as we had a little money from the University of Birmingham via the Birmingham Voluntary Services Council to work together on research. Another blog on the research work will be published at a later date.

On the 17th of July, BHCF were fabulous hosts and participants in a daytime event bringing together people from a wide range of contexts. In addition to those with knowledge from the city farm, we had researchers, educators, and practitioners join us (including those from Equine Science, Assistance Dog training, Equine Assisted Therapy, and Social Work).

Two goats on straw in the stable at BHCF. There's a salt lick hanging down and hay (and just in sight, water) for them too.

The Aim was to offer a space where relationships could begin to be developed to support the production of more research that can help us understand how to maximise human and non-human animal welfare and well-being in relation to animal-assisted interventions. It was also a space where people could think about their work and how they might want to develop it further through learning from others in the room.

As a group, we recognised that historically, within Western knowledge traditions, we have a long thread of humans being understood as separate from nature, including from other animals. For some people, there is a political and existential reason to challenge this (e.g. an argument that climate crisis cannot be averted if humans are not prepared to engage with their place within the natural world). We can look to traditional and indigenous forms of knowledge that counter the human exceptionalist approaches which (in the light of ecological concerns) have become more pertinent including in being used critically within and alongside scientific work. Interdisciplinary work in ‘animal studies’ and developing sub-disciplines such as ‘anthrozoology’ reflect this. Some of us also shared how writing about plant life by Robin Wall Kimmerer demonstrated how indigenous and scientific knowledge could be brought together to help us engage with the natural world.

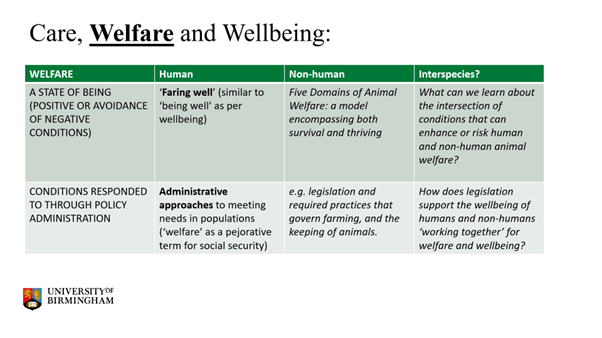

obin Wall Kimmerer's 'Braiding Sweetgrass', a Penguin book which has 'A hymn of love to the world' as a quote at the top from Elizabeth Glibert. A braid of grass runs across the centre of the book cover, underneath the main title. Subtitle is 'Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants'. Is Welfare Enough? An essential thread in the day’s discussions was the extent to which ‘welfare’ often only comes into view when there are concerns about minimising harm – particularly when there is some kind of exploitation of someone’s or something’s value. This meant that we recognised that ‘negative welfare’, when basic needs aren’t being met, has often been a policy focus. There was consideration of the extent to which legal requirements about conditions only developed when there was concern about harm (rather than looking to ‘positive welfare’ – or even wellbeing). What is deemed acceptable in welfare terms (for humans or non-human animals) in terms of space, nutrition and opportunity to move and interact with others might be describable and measurable (but also malleable – e.g. may change over time or between contexts).

We moved on from the limited ‘minimum conditions’ sense of welfare to look at more positive ways of looking at interspecies welfare (and moving towards a consideration of wellbeing). One Welfare (https://www.onewelfareworld.org/) is a valuable approach for engaging more relationally with how different species interact, seeing the welfare of humans as interconnected with the welfare of animal lives. Of course, we can determine how many animals experience their lives as we ‘keep’ animals for food, transport, leisure, or other animal-based activity (e.g. sport, therapy). The Five Domains was also considered – an approach used to support work around animal welfare, with a strong focus on positive states, and the contribution of four domains (Nutrition, Environment, Health and Behaviour) to the fifth (Mental State). This approach has been particularly valuable in supporting the development of welfare-focused practice and welfare outcome measures. Plenty of organisations (as well as academic texts) provide detail – for example, see this from Redwings Horse Sanctuary (including a lovely image, but I wasn’t sure about copying it into my blog, even with a good citation!).

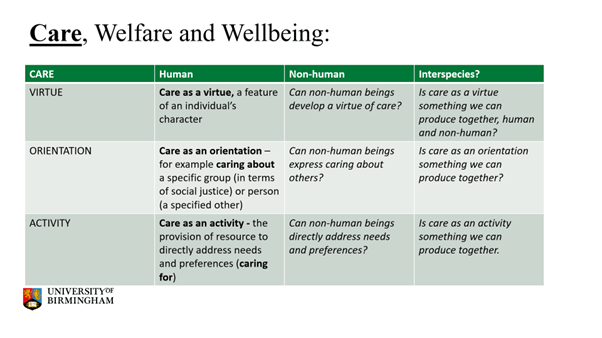

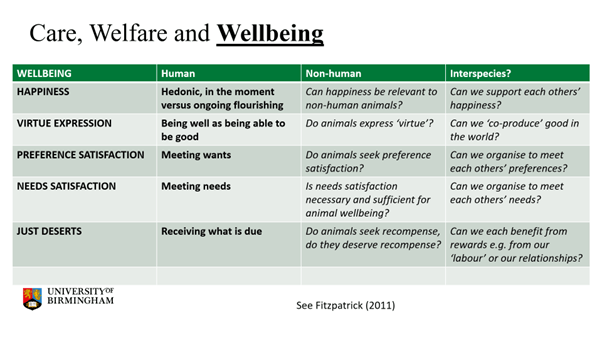

This was all a bit of a springboard towards thinking about whether or not we are speaking the same language (e.g. in human-focused work and animal-focused work) when we talk about care, welfare and wellbeing. I enjoyed hearing others’ knowledge, experience and motivation. Different frames of reference were brought together – from keeping and training animals to observations of non-domesticated animals in their open (but often human influenced) environments. When trying to think about animal welfare and wellbeing, we considered whether we can empathise with non-human animals (and perhaps there are ways in which anthropomorphizing can be useful, as well as having downsides?).

I didn’t need to bring much of my own work in because there was so much to be excited about in the room from considering the life course experiences of assistance dogs to exploring how animals (such as horses) might be educational supports for students. There is so much to say from work with BHCF that will be explored in my later post. By way of example, specific benefits that could be illustrated from my work with BHCF included how ‘small furries’ could help people self-regulate, not as an ‘intervention’ in a formal sense, but through being available within the community as a resource where you get a chance to feel different and more present than you might have the opportunity to in your day to day life. The power of guinea pigs to help with this was really well communicated to me in fieldwork (by a BHCF volunteer), a reminder that you don’t have to be a half-tonne horse to be a useful animal in animal-based support for human lives.

Thanks to all who participated – I’ve not taken anyone’s name in vain, but if you were there, feel free to offer comments below or (attenders or not) do email me if you are interested in being part of a network on human / non-human animal wellbeing – h.clarke@bham.ac.uk

I just want to finish with a quote from Sunaura Taylor which for me captures why care, welfare and wellbeing through an interspecies lens seems such a valuable part of what it is to be a human in a more than human world. Even though it may often be awkward and imperfect, let us care for each other as humans and non human animals experiencing and acknowledging our interconnections.

Bailey is still my service dog, attentive to my emotions, needs and whereabouts, his very presence helping to mediate between me and the ableism I encounter when we go on our daily walks together. And I gladly embrace being his service human as much as I can. … Two vulnerable, interdependent beings of different species learning to understand what the other one needs. Awkwardly and imperfectly, we care for each other.

Note: if you want to read more the PowerPoint I used on the day can be accessed via the link labelled "interspecies perspectives on care welfare and wellbeing' below. I've also popped some pictures of slides below incase that helps you decide if this interests you further. Some resources are at the bottom of this page. I'll be writing up the work Balsall Heath City Farm and I have been involved in together as soon as I can.

Biblography

Madden, R. (2014) Animals and the Limits of Ethnography, Anthrozoös, 27:2, 279-293, DOI: 10.2752/175303714X13903827487683

Fitzpatrick, T. (2011) Welfare Theory: An Introduction to the Theoretical Debates in Social Policy, Bloomsbury.

Sopel, D. (2021) Moving to the ‘Five Domains’ model for assessing animal welfare (wcl.org.uk) (Accessed July 15th 2024)

Taylor, S. (2017) Beasts of Burden: Animal and Disability Liberation, The New Press.