Flying to Flyinge as a social scientist…

Flyinge Kungsgård have just hosted (September 2024) the ‘Horse Welfare Summit‘, which – immediately after the Paris 2024 Olympics and Paralympics, has occurred at an exciting moment in developing horse welfare knowledge, practice and – yes – debate. I attended this conference as part of my ongoing research on involving non-human animals in human well-being initiatives (especially equine-assisted services and care farms/city farms). I am interested in how we keep and use animal lives, including how horses can be used (and indeed misused) for various human wants and needs. The possibility of producing better – more ethical – ways of working with non-human animals keeps me hopeful that change should be worked towards and that this cannot solely be in one sector – we need to look across sectors to understand how human and non-human animal lives intersect and can be improved.

Given my academic and practitioner interests in multispecies welfare and care—from social science and psychotherapy perspectives—I take steps to learn from animal-focused contexts and disciplines. In addition to attending online seminars and taking every opportunity to learn from those with animal expertise, engaging in in-person environments nourishes me intellectually (and thankfully helps develop relationships). The Flyinge event was equine science and equestrian industry ‘heavy’ (in a good way), with some social scientists, historians (and indeed some cross-disciplinary equestrians!) engaging within the space. Philosophically, there were threads present concerning what constitutes knowledge (e.g. what role can autoethnography play, how might AI improve our understanding of the welfare of the horse … and more) which fuelled my research methods interests – and substantively, there was much to be gained too.

As a ‘human’ social scientist (for 30 years), I know that focusing on animal welfare without engaging in human welfare concerns can often leave me feeling like I’m not doing my job! After reflecting on some specific horse welfare-focused sessions below, I will discuss more of that (which I hope addresses why animal welfare is relevant to human lives).

Professor Nat Waran – The Uncomfortable Truth Professor Waren (a member of the FEI Equine Ethics and Wellbeing Commission) emphasized the risk of losing public support for horse sports if welfare concerns for equines are not addressed.

She had no doubt that this was an urgent issue for equestrian sport.

She urged those working with horses to consider not just basic needs but also emotional indicators of positive experiences for horses.

As someone from a human-focused discipline, I find it essential to consider both horses’ and humans’ well-being together. Therefore, I valued being able to ask about her experience of working with different stakeholder concerns (needs and wants) and their perspectives to bring about change. It sounds like a very sensitive process, albeit enabled through the organising support of the FEI. There were also some pointers towards some exciting areas for ‘interspecies’ exploration – for example, Waren shared that public sentiment for horses, as majestic animals, might mean worries for horses gain particular traction. This highlighted that our concern for horses could be at the expense of less visible and/or relatable species.

Jessica Stark – Equestrian’s Social License – What does it have to do with me? Jessica Stark is the Director of Communications and Public Affairs for World Horse Welfare and a member of the FEI Equine Ethics and Wellbeing Commission. World Horse Welfare’s role in promoting the horse-human relationship speaks so clearly to my interests, as does its determination to work with Governments, Universities, and other organisations to improve both human and animal lives and livelihoods.

The charity was founded in 1927 and focuses on caring for horses in need (sport and leisure horses and those involved in other productive work). Their work involves research, education, and trying to impact others’ (including sports organisations’) policies and practices.

Jessica presented attitudinal research evidence from the public and from equestrians (in the UK and around the world); it was also significant (I think) to be reminded that 80 per cent of the world’s horses are still in utilitarian work. Given we were at a Horse Welfare Summit, it was helpful to be lifted to look beyond sports horses to recognise the contributions and perhaps welfare concerns for the horses that transport, or that plough, or who help to provide therapy? Maybe the public is most concerned about the horses they are shown the most (aka those in sports), more so than those working in other roles. To what extent should it matter to us that an equid is helping humans maintain subsistence (rather than being part of quite a lucrative industry in top-end horse sports)?

World Horse Welfare—and others researching and working internationally around equids that work—have a lot to teach us about considering our ethics across different domains. Listening to Jessica and trying to attune myself to learn from those from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland while I was there reminded me to try to avoid being parochial.

Professor Kendra Coulter – Solidarity with Horses Kendra Coulter is Professor in Management and Organizational Studies at Huron University College at Western University, Canada. I have already enjoyed reading her work – and am glad to have more to explore. Her research helps us distinguish between work on, with, and for animals. She highlighted that it can be unhelpful to talk about the horse industry—there is so much diversity, and horses in many varied settings are so differently valued.

Coulter helped us consider how, for example, horses’ lives are impacted by the country they live in (the laws/policies), the sector they work in, their living conditions and owner/manager philosophy, and their life course and stage of life. This last point really chimed with me: for example, I’ve found it difficult to hear how racing is improving concerning welfare when we know how young those horses are backed, and when we can try to empathise with what it might be to be a youngster placed into those settings (never mind getting to the implications of an early intensive start on future life possibilities).

Professor Coulter also highlighted how horses have their own personalities, opinions, voices, and agency. We impose identities (such as leader, friend, meat, co-therapist, and so on) on the horse, reflecting that horses fulfil more roles for us humans than any other animal. However, this is not always reflected in the level of consideration we give to them as sentient beings.

Next, horse welfare was contrasted with well-being (bringing in more consideration of emotion and relationships). What though about Horse rights? And horse flourishing? I feel these are useful, but as Kendra responded to me in later questions, there is a wall you might put up between yourself and others if you talk of animal rights.

It was great to hear that Martha Geiger is working with Kendra Coulter on the Horse Harm Spectrum (or Continuum) to help represent complexity (which includes that horses experience physical and psychological pleasure and pain, that boredom is problematic, and that harms can be overt or subtle—and indeed illegal or legal).

Kendra then expanded on solidarity—how it is rooted in empathy, concerns supporting the other despite differences, and requires action. Solidarity is a process. The inherent value of horses (beyond their instrumental value for us) can be brought to the fore and help us consider the well-being of horses (not only those we know and love).

Professor Kendra Coulter – Lifting Horses – The Practical use of Ethics in Stables Kendra presented twice at the conference – here, I was so pleased to see a range of academic disciplines – and interdisciplinary fields – highlighted as producing material relevant to practice (but not always difficult to take from academia to the ‘field’ (or stable). It was stressed that science, social science and ethics must all be engaged together to work towards better lives for horses. I think all of us with horse experience – whatever our background – would recognise how horses expressing their opinion and agency was represented (e.g. kicking, biting). I strongly agree with Kendra Coulter’s posing the question of what should happen when a horse doesn’t like their job, if they hate their job can we help them find another one? How much do we consider not just their days but their life course-related needs? This led to the consideration that there can be financial issues or economic arguments that people might put forward (or a sense of entitlement perhaps) to argue that a horse should do the job asked of them. (Here is one of the moments I felt the ‘it happens to humans too’ internal voice that kept popping up during the two days!).

Nina Känsälä – You and Me – Horse welfare in everyday life with horses I attended a very engaging round-table session where we worked together in small groups to explore the threat to equestrian supports (given concerns about social licence to operate), welfare issues in equestrian sports, how they were understood, and what might be done about them. Nina Kansala – who is undertaking a PhD on Social Licence to Operate at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences – foregrounded our work by discussing the military history of equestrianism and how it is associated with tradition and conservatism. She prompted us to consider whether people ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ the horse world had different lenses,

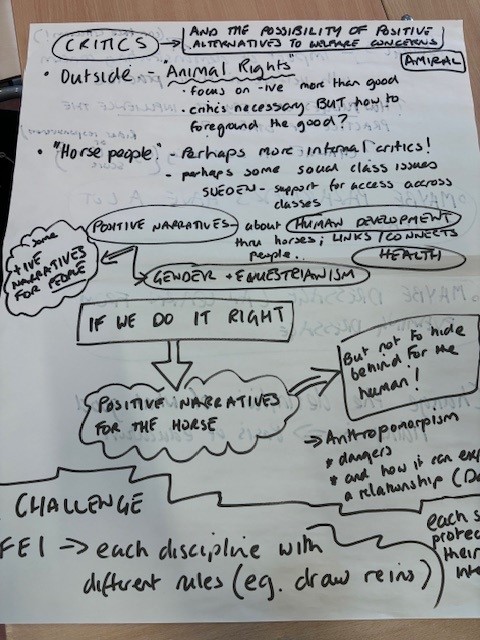

The image above provides a photo of flip chart writing which summarised of some of the discussion from the round table work (expanded on in the text below). We explored how critics from the outside are often coming from an ‘animal rights’ perspective; some of the biggest critics of equestrian sports can come from within the field; issue of conservatism and tradition and how that plays out in different country contexts addressed by discussion of how Sweden increases access to horse sports (compared to many countries) because of how children are invested in including in relation to sport. This can mean that engagement with horses connects more people in some countries (e.g. Sweden) than others.

Positive narratives for the human around horse sports include in relation to health, personal development, access to gender neutral competition. Our table also wondered how we could develop positive narratives for the horse, not hiding behind anthropomorphizing the horse but recognising them as a sentient being. Challenges include each discipline within the FEI having different rules about what is and what is not allowed (e.g. draw reins).

Some exciting additional points were made including whether sports disciplines could change how they are scored (e.g. to include a welfare component, or through use of AI to assess horse welfare). There were also specific questions concerning whether parariders could teach equestrianism in general some interesting lessons about equine welfare, and whether event dressage also might have some valuable insights to provide.

A final point was whether we need to change the agreed definition of what constitutes good riding, and have this as the basis of education. This sounds, to me, like it requires an interspecies perspective!

Interspecies Insights (and why Social Policy remains my ‘home’ discipline)

The conference presentations and conversations reinforced my commitment to “bringing the (non-human) animals in” more prominently into social policy-relevant research and discussions. They also helped strengthen my motivation, which includes contributing positively to our knowledge and understanding of human lives to inform policy and practice. Interspecies solidarity, as offered by Coulter, appeals to me as it enables us to ensure that human lives are part of the picture when we bring the horses (and other animals) forward for consideration. She also helpfully highlighted how the human welfare discourse in Sweden could be contrasted strongly with those from other settings.

When I contrast the ‘horse welfare’ discourse with the ‘human welfare’ discourse (at least that which I know in the UK), I experience some sadness. Whilst committed to positive animal welfare, I am frustrated that I do not believe we give sufficient attention to the emotional state of humans. In this sense, the parallels between many human and animal lives are worth examining (Sunaura Taylor – see https://thenewpress.com/books/beasts-of-burden – has produced such fabulous work achieving this).

Human lives don’t all have the same opportunity to be heard; some humans are often ignored. Human lives are not all valued equally, despite conventions on human rights. When Professor Waren talks about what has become normalised in the equestrian world (spurs, for example) – this reminds me to question what has become normalised in the human world (for instance, some of us might argue that there are harmful ‘nudges’ in social security systems and in human employment that can leave physical harms as well as emotional and relational distress amongst us humans). Perhaps the attention given to listening to animals by those seeking to protect the horse sports world should jolt us into re-asserting that human lives require much more detailed consideration and compassion in how we organise our economic and social world – for one another’s physical welfare, for wellbeing, and yes some (many?) of us would say for flourishing too.

Some questions I’m left with that feel exciting, interesting and hopefully at least potentially important include:

- how do our human welfare discourses and policies influence the extent to which research communities (and others) might be open to engaging with interspecies solidarity as an approach?

- can debates about animal welfare and well-being open up or inform claims about human welfare and well-being (and vice versa)?

- can human and non-human animal lives be explored through a shared framework (possibly encompassing welfare, wellbeing, flourishing and rights)?

I’m also left with gratitude for the conversations I had with people who were prepared to share the import of horses in their lives—sometimes very much indicating that human well-being is not always secured in human-only environments. Whilst horses are often associated with risk, they can also be felt as a place of safety and as animals that support our growth and development in ways that human-only spaces don’t manage for all of us. This is why equine-assisted therapy and learning are also of significant interest!